The term turnout ballet describes the physical action of turning out your leg from your hip joint. This technique moves your weight from one foot to another and enables you to dance gracefully and efficiently. However, some ballet dancers complain that turnout causes plantar fasciitis. This article will discuss what you should know about turnout ballet. It will also give you a basic understanding of how to prevent it from occurring to you.

Turnout is a physical representation of giving.

The concept of turning out in ballet dates back to Louis the XIV. The purpose of this movement was to help dancers balance on raked stages and make weight transfer easier. Turnout has since become a part of ballet’s allure, and dancers strive to achieve a 180-degree turnout. Unfortunately, the ability to achieve this position is not very common.

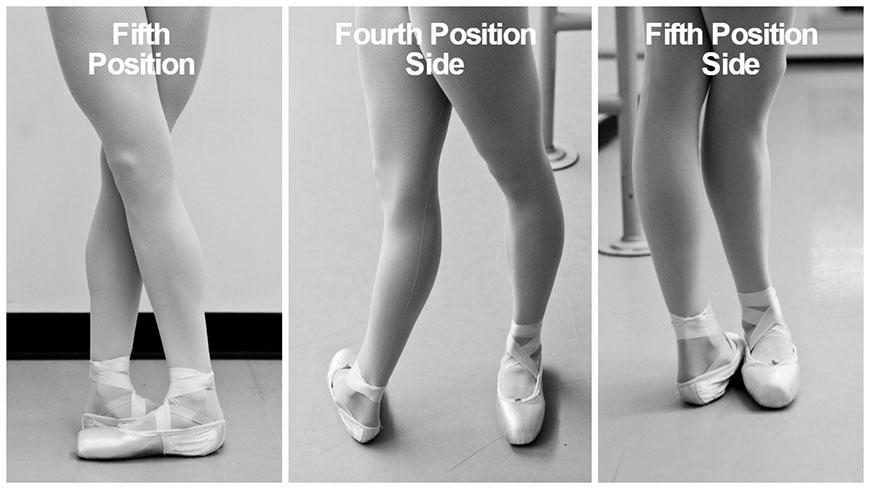

The basic technique for turnout involves external rotation of the leg, which begins from the top of the leg. Turnout is a series of turns involving the hip, thigh, knee, ankle, and foot. Many professional dancers demonstrate that most outward rotation is generated in the hip joint. While bone structure cannot be changed, soft tissue can adapt and bias hip rotation. Xiomara Reyes, the creator of Turnout ballet, compares this movement to the process of a rose blooming from the inside out.

A good turnout is an angle between the center lines of the feet when the heels touch. This angle is difficult to achieve without proper conditioning. Different exercises increase hip mobility and elasticity and strengthen the buttocks muscles. A good turnout is also completed with proper rotation at the hips, which is one of the critical components of the technique. However, this position is often accompanied by a high risk of injury.

A detailed discussion of hip ligaments is provided later in this chapter. The extensibility of hip ligaments is another critical factor in improving turnout. External rotators should be strong, and the iliofemoral ligament is taut at the end range of external rotation. Developing a solid external rotator helps a dancer achieve its full potential in turnout. Turnout in ballet is a physical representation of giving.

It transfers weight from one foot to another.

Turnout is when the dancer transfers weight from one foot to another, externally rotating that foot. The externally rotating motion of the leg is caused by nearly all bones, including those of the femur, tibia, ankle, and foot. Turnout is accomplished through the rotation of relevant joints, which include the hip and knee joints, the joint between the spine and sacrum, and the ankle.

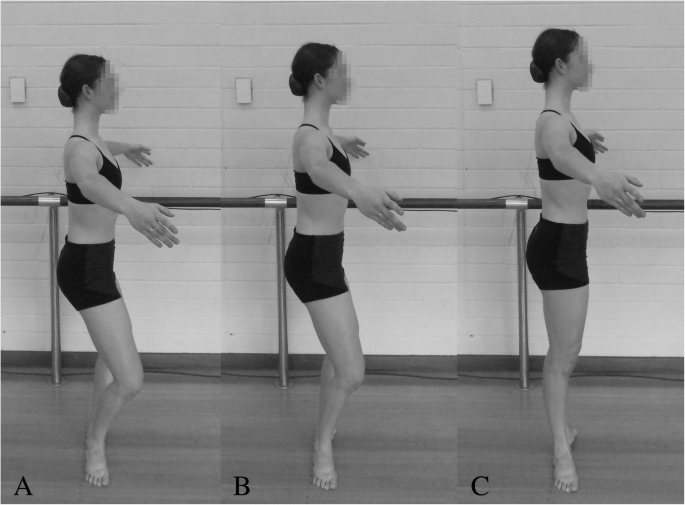

To begin, the unweighted foot lifts from the floor, making light contact with the floor. The receiving foot rolls through to the floor, so the heel first makes contact with the ground. Timing of the weight transfer is not as important as the start and end positions, but the foot must be straight when the heel contacts the floor. The weight transfer should occur before the foot rolls through to the floor so that the weight of the unweighted foot will not be on the receiving foot when the heel is released from the floor.

It allows dancers to move gracefully and efficiently.

The primary muscles in turnout are the six deep external rotators located below the gluteus maximus. Turnout requires efficient movement of these muscles, which helps dancers turn out gracefully—practicing these muscles before a ballet performance will improve the efficiency of their actions. Once these muscles are strong and coordinated, they will be used in many ballets and contemporary dances.

There are a few critical physical requirements involved in turnout ballet. These include ‘flat’ turnout, which consists of the rotation of the hips to align with the femur. A flat turnout requires precise muscle movement and is the key to a ballet performance. The correct form is essential to avoid injury. There are several ways to perform ‘flat’ turnout, including extending the toes with tensed arches.

It causes plantar fasciitis.

If you’re a dancer, you’ve probably heard of the condition known as plantar fasciitis. This condition is a painful inflammation in the tissue that runs along the mid-arch of the foot. It’s usually red and warm to the touch. The situation is often said when the dancer bends or straightens their big toe. Fortunately, there are several ways to avoid developing this condition.

The first and most common solution to plantar fasciitis is to stretch. While you’re dancing, feel for a stretching sensation along the heel and arch of your foot. Repeat the stretching routine three or four times a day. Please do not overdo it, as you may injure yourself. If your pain continues, seek medical attention. You might have plantar fasciitis due to overexertion.

This condition is caused by overuse of the plantar fascia, a brutal band of tissue that connects the heel bone to the base of the toes. The plantar fascia can become inflamed and painful if not supported by proper footwear. The pain and swelling occur at the inside bottom of the heel and the arch area. Treatment for this condition involves stretching the gastrocnemius complex, taking anti-inflammatory medication, and wearing supportive footwear outside the studio.

The biomechanical theory of the ankle’s movement suggests that ballet dancers compensate for limited hindfoot eversion through increased passive external tibiofemoral rotation. This compensatory mechanism is based on current biomechanical theories that indicate that the body transfers compensation to the following mobile joint in a closed kinetic chain. Unfortunately, this faulty biomechanical approach is associated with a high risk of injury.