What does turn out mean in ballet? Turning out is a movement in which the leg rotates at the hip. This movement is a functional representation of reaching the audience. But it can also be painful to the knees. This article will explain the term and its meaning in ballet. Let’s start by defining it. Turnout is a leg rotation from the inside hip to the feet.

Turnout is a rotation of the leg at the hip.

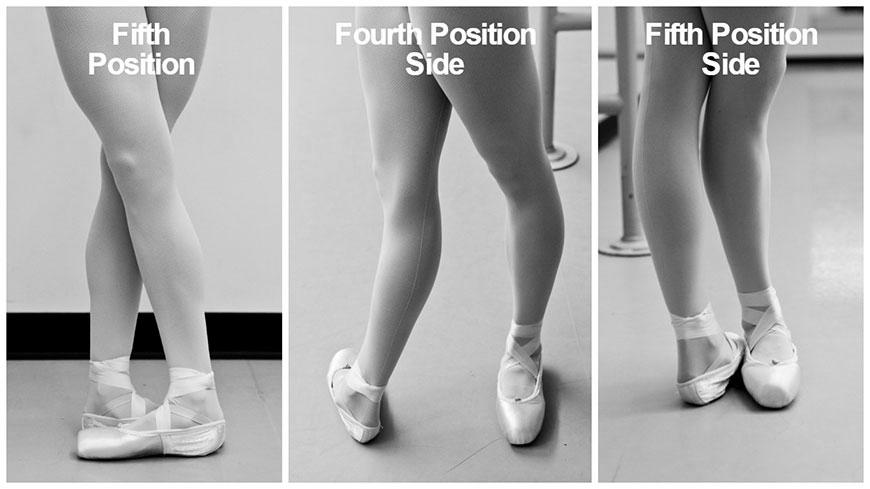

The term “turnout” refers to the external rotation of the leg at the hip. Turnout is initiated at the top of the leg and involves the hip, thigh, knee, ankle, and foot. Many professional dancers demonstrate that most outward rotation occurs at the hip joint. While bone structure cannot be changed, soft tissue can be trained to accept slight hip rotation. Xiomara Reyes compares turnout to a rose blooming from the inside out.

This position puts the dancer at risk for a low back injury. Although many ballet dancers have a history of softback injury, limiting the turnout to less than 90 degrees is generally not a good idea. Ballet teachers should encourage students with a compensated turnout to reduce their turnout and increase strengthening and stretching exercises to improve the external hip rotation. While many dancers will never reach the ideal turnout, they can continue enjoying ballet practice.

A dancer’s turnout depends on their particular anatomy and technique. At the hip joint, about 60 percent of turnout comes from the hip, while twenty to thirty percent comes from the ankle. The remaining 30 percent is from the knee and the tibia. Unlike ankle-to-ankle rotation, turning from the hip is safer. It also requires specific muscles to support the process. The lateral rotators pull out the greater trochanter while the sartorius keeps the tibia while the inner thigh muscles help stabilize the pelvis.

Overcompensation is a common dancer injury that limits turnout. Excessive compensation can cause the tibia to grow out of alignment with the femur. Tibial torsion results from turning out too far and can prevent a dancer from performing well. It is also a severe training error because excessively compensated turnout will impede physical performance.

It is a functional movement.

There are two basic types of turnout: compensated and functional. A compensating turnout increases external hip rotation by anteriorly tilting the pelvis. During this movement, the acetabular shelf is more profound on the posterosuperior side than the posteroinferior side. While compensating turnout may increase external hip rotation, it puts a dancer at greater risk for injury.

A dancer attempting to turnout must be aware of the risks involved. Overturning the foot and leg in excessively high rotation may lead to a tibial torsion, which is an injury and can inhibit physical performance. Additionally, turning out too far may involve gripping the toes or tensing the arches of the foot. Both of these techniques can cause serious injuries.

An excellent turnout in ballet is 180 degrees. However, this degree of turnout is unnatural for the body and must be trained into a dancer’s muscles. A 180-degree turnout requires training, which is more important than its degree. Incorrect use of the turnout can lead to injury and compromise a dancer’s technique. While this is an ideal goal, it’s not a necessary prerequisite for proper procedure.

A correctly performed turned-out requires a strong foot. The foot muscles help support the foot arch and correct the lower extremity alignment. To achieve a stable turned-out, a dancer needs sufficient dorsiflexion of the foot and an angle of 90 degrees in the Achilles tendon. A tight calf and inflexibility of the Achilles tendon can limit this movement. Pronation, on the other hand, increases the depth of the plie and places the Achilles tendon on slack. Additionally, this movement can change the alignment of the bones and soft tissues.

It can cause knee pain.

Being turned out in ballet can lead to knee pain mainly due to improper alignment and muscle imbalances. This is especially problematic for young dancers, as they may use forceful turnouts that put unusual stress on their joints. Proper alignment and control are essential for turning out properly, and this requires strong core muscles, balanced quadriceps, and hamstrings, as well as appropriate placement and positioning.

The hip joint’s external rotation is tested when a dancer is prone or on her stomach. Overturning the hip can cause knee pain. To avoid this, turnout must be performed with a natural turnout of 48 degrees. Fortunately, proper turnout can be taught to all dancers, and professional ballet teachers provide cueing that teaches dancers the correct technique. If knee pain persists, medical treatment is recommended.

During a dancer’s plie, the patella is rotated by 65 degrees and not tracking properly in the patellar femoral groove. The patella must tilt slightly to stay upright. This side-to-side motion can cause excessive external rotation of the knee joint and wear down the cartilage on the underside of the patella. Ballet training programs provide a safe way to prevent injury and keep dancers moving correctly.

Injuries to the knees are not unusual in the dance industry. The primary cause is awkward landings, but dancers can also experience sprains, fractures, and torn ligaments. A torn meniscus or ligament in the knee is extremely painful, and dancers should seek medical attention if they feel pain in their knees. Physiotherapy is often necessary for the rehabilitation of knee pain. A doctor will recommend a reduced activity level until the knee heals sufficiently. An MRI will confirm whether the injury is severe or not.

It is okay to force turnout.

Many dancers force turnout and end up in an awkward and painful position. But it’s important to remember that the most famous ballerinas had no perfect turnout. Even Margot Fonteyn was not without a lousy turnout. The main reason for poor turnout is the strain it places on the big toes, and forcing turnout can also hurt your alignment and cause knee pain.

There are times when forcing turnout is necessary. For example, during arabesque, the foot should turn out. Forced turnout is not recommended during tendus or degage. This is because it will not work correctly and will cause injury. In addition to this, moving turnout will decrease your flexibility. So if you are forced to force turnout, follow the instructions carefully. A proper turnout will allow you to perform all the steps you learn.

Good turnout requires both precision and hard work, and it is crucial to avoid any injuries. A passionate student will find the drive to persist even when they are not perfect. While it is important not to force turnout, a professional ballet teacher will provide you individualized attention. You may ask an experienced dancer for advice. It is important to remember that professional ballet teachers charge a higher rate for group lessons than for classes.

Performing forced turnout causes several issues for your body. When you force turnout, you put extra pressure on bones, ligaments, and muscles, which may cause problems. You may also develop plantar fasciitis if you grip the floor too hard during relieves and jumps. Furthermore, forcing turnout causes pressure on the big toe joint, leading to pain, irritation, and, in severe cases, a bunion.